In this article we will build a simple command line program that accesses a database. The program we are going to write will keep track of a reading list. We’ll tell it about the books that we’re reading or about to read and it will display that information in various lists. Next month we’ll make the program into a web application.

Setting up the database

Firstly, we’re going to need a database to store this information in. I’m going to use MySQL as it’s the most widely available database system, but the same code will work with minor amendments with any other relational database.

We’ll store the data in two tables – author and book. In the interests of keeping things simple we’ll ignore books with multiple authors.

First we’ll create a new database to contain the tables and switch to that database.

|

1 2 |

create database if not exists books; use books; |

We’ll also create a user for our application. You might want to change the password. If you do, you’ll need to also change it in the get_schema() subroutine (defined below) as well.

|

1 2 |

create user 'books'@'localhost' identified by 'README'; grant all privileges on books.* to books; |

The author table is very simple.

|

1 2 3 4 |

create table if not exists author ( id integer primary key auto_increment, name varchar(100) ) engine innodb; |

The “engine innodb” is important as that means that we can give these tables constraints that define the relationships between the tables. We’ll see that being used in the book table.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

create table if not exists book ( id integer primary key auto_increment, isbn char(10), author integer, title varchar(250), started datetime, ended datetime, image_url varchar(250), foreign key (author) references author (id) ) engine innodb; |

The foreign key line at the end of the definition says that the author column in the book table contains values that are equal to the id column in the author table. So if Douglas Adams has the id 1 in the author table then the record in the book table for The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy will have a 1 in its author column. Splitting the author out into a separate table means that we can store information about several Douglas Adams books in the book table without duplicating the information about the author. Avoiding data duplication is called “normalisation” and is an important topic in database design.

Enter DBIx::Class

Having created our database, we now want to set up some Perl code to talk to it. We could use the DBI (Database Interface) module and write raw SQL. But no-one likes writing SQL so we’re going to use an “Object Relational Mapper” (or ORM) to convert Perl code into SQL. This will make our code much easier to write at the cost of a small amount of set-up.

The ORM we are going to use is called DBIx::Class so we’ll need to ensure we have that module installed. We’ll also need a separate module called DBIx::Class::Schema::Loader which can generate Perl libraries that are specific to our database. You can probably install both of these libraries using your distributions packaging tools, but if they aren’t available you can get them both from CPAN.

DBIx::Class::Schema::Loader comes with a command line program called dbicdump which will look at the tables in your database and create the Perl code needed to manipulate those tables. You run it like this:

|

1 2 |

$ dbicdump -o components='["InflateColumn::DateTime"]' \ Book dbi:mysql:database=books books README |

The -o components option loads some extra functionality that we’ll see later on. ‘Book’ is the name of the Perl module you want to create. Then there is a Perl DBI connection string which includes information about the type of database we are talking about (mysql) and the actual database that we’re interested in (books). The last two arguments are the username (books) and the password (README).

When you run that command you’ll find in your current directory a new file called Book.pm and a new directory called Book. Within the Book directory you’ll find another directory called Result and within that, there are two files called Author.pm and Book.pm. If you look at the contents of these last two files, you’ll see code that closely matches the definitions of the two tables in your database.

Setting Up the Amazon API

There’s one more thing that we need to do before starting to write our program. We’ll be using the Amazon API to get various details about the books in our database, and we need to register for an API key in order to use the API. You can register for a key at:

www.amazon.com/gp/aws/registration/registration-form.html

Once you’ve signed up you can go to the ‘Security Credentials’ part of the site to get your Access Key ID and Secret Access Key. I recommend setting environment variables to these values like this:

|

1 2 |

export AMAZON_KEY=[Your key here] export AMAZON_SECRET=[Your secret key here] |

Finally Some Perl

Finally, we’re ready to start looking at the program. We’re going to create a program called book that has four sub-commands. Typing book add <ISBN> will allow us to add a book to our reading list. Typing book start <ISBN> will flag that we’ve started to read a book and book end <ISBN> will flag that we’ve finished it. At any time, typing book list (or just book without a sub-command) will display the list of books in our database, indicating which ones we are currently reading and which we have finished.

The start of the program looks like this.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

#!/usr/bin/env perl use strict; use warnings; use 5.010; use Book; use Net::Amazon; use DateTime; |

A lot of this will be common to every Perl program that you write. The first line is the “shebang” line. This tells the Linux shell to run this program using the Perl compiler. The next two lines load two standard Perl libraries called strict and warnings. Think of these as programming safety nets. The most important thing that the strict library does is to force you into declaring your variables. The warnings library looks for a number of potentially unsafe programming practices and displays a (non-fatal) warning if it finds any. No serious Perl programmer writes programs without loading these two libraries.

The third use statement is slightly different. It doesn’t load a module, but tells Perl that this program needs to be run on a particular minimum version of Perl. We’re forcing the use of at least Perl 5.10 as we’re going to use the say() function that was added in this version.

The following three lines are back to loading libraries. Book is the library that we created to talk to the database. Net::Amazon is the library that we’ll use to talk to the Amazon API. And finally, DateTime is a powerful Perl library for the manipulation of dates and times.

Making sense of input

The next thing we need to do is to work out which of the sub-commands has been invoked and run the appropriate code.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

my %command = ( add => \&add, list => \&list, start => \&start, end => \&end, ); |

This statement defines the valid sub-commands that our program will implement. It does this by setting up a hash (or dictionary) called %command. The % at the start of a variable name indicates that it is a hash. A hash is like a look-up table. It has keys which are associated with values. In our case, the keys are the names of the sub-commands and the values are references to the subroutines which implement those commands. Putting an ampersand on the front of a subroutine gives us a way to refer to the subroutine without executing it and a backslash is the standard Perl syntax to get a reference to something.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

my $what = shift || 'list'; if (exists $command{$what}) { $command{$what}->(@ARGV); } else { die "Invalid command: $what\n"; } |

The next few lines deal with the command line options and calling the appropriate subroutine to do the work. Command line arguments to a Perl program are stored in an array called @ARGV (the @ indicates an array in the same way that a % indicates a hash). The shift() function removes the first element from an array and returns it. You’ll notice that we don’t give shift() an argument. That’s because of its special behaviour. If you call shift() without an argument outside of a subroutine then it will work on @ARGV by default.

If we haven’t been given a command line argument then @ARGV will be empty and shift() will return a false value. In this case, we want to act as if the user gave us the sub-command ‘list’. The || operator lets us do this. This is the Boolean ‘or’ operator. It returns its left operand if that value is true, otherwise it returns the right operand. So if there’s a value in @ARGV we get that, otherwise we get ‘list’. The value calculated from that expression is stored in $what (Perl scalar variables begin with a $).

Having got the sub-command, we now need to know if it’s a valid value. We do this by looking in the %command hash. We use the exists() function to see if $what matches one of the keys in the hash. If it does we call the appropriate function, if not we die with an appropriate error message. Notice that as the hash contains subroutine references, we need to call the subroutine using a dereferencing arrow. Also, notice that we pass what is left of @ARGV on to the function that we are calling. In some cases, it will be empty, but in others, it will contain the ISBN for a book.

The Meat of the Program

That’s the main structure of the program complete. All we need to do now is to implement the various subroutines that do the actual work for the various sub-commands. Before we start those, we’ll write a useful utility subroutine that they will all use.

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

sub get_schema { return Books->connect('dbi:mysql:database=books', 'books', 'README') or die "Cannot connect to database\n"; } |

All of the commands will need to communicate with the database. When using DBIx::Class all communication with a database is carried out through an object called a schema. Our get_schema() function just connects to our books database (using the Book module we created earlier). If it can’t connect for any reason, it just kills the program with an error message.

Adding Books to the List

The first sub-command we will look at is the one to add books to the database.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 |

sub add { my $isbn = shift || die "No ISBN to add\n"; my $schema = get_schema(); my $books_rs = $schema->resultset('Book'); if ($books_rs->search({ isbn => $isbn })->count) { warn "ISBN $isbn already exists in db\n"; return; } my $amz = Net::Amazon->new( token => $ENV{AMAZON_KEY}, secret_key => $ENV{AMAZON_SECRET}, locale => 'uk', ) or die "Cannot connect to Amazon\n"; my $resp = $amz->search(asin => $isbn); unless ($resp->is_success) { say 'Error: ', $resp->message; return; } my $book = $resp->properties; my $title = $book->ProductName; my $author_name = ($book->authors)[0]; my $imgurl = $book->ImageUrlMedium; my $author = $schema->resultset('Author')->find_or_create({ name => $author_name, }); $author->add_to_books({ isbn => $isbn, title => $title, image_url => $imgurl, }); say "Added $title ($author_name)"; return; } |

We need the ISBN number of the book to add. This is passed as a parameter into the subroutine. Perl passes parameters into subroutines in an array called @_. In the same way that shift() works on @ARGV when called without an argument outside of a subroutine, it works on @_ when called without an argument inside a subroutine. If no value is found, then the program dies.

Having got an ISBN, we first need to check that the book isn’t already in the database. We get a schema object and use that to give us a resultset object for the book table. In DBIx::Class, all manipulation of a specific table is done using a resultset object. We can use the resultset’s search() method to look for books with the same ISBN. The search() method returns another resultset object and we can use the count() method on that to see how many books already exist in the database with this given ISBN. Hopefully, there aren’t any. But if there are, we can display an appropriate message and return from the subroutine without doing any more work.

If the book isn’t already in the database, then we can add it. But first we need to get more details from Amazon. We create a Net::Amazon object giving it the key and secret that we got from Amazon. We also set the locale to ‘uk’ so indicate that we want to use Amazon’s UK data. We can then use the search method on the Amazon object to look for products with our ISBN. If the search is successful, we can get details of the matching book from the returned object.

Having got the details of the book, we can extract various interesting things from the object and store them in our database. Notice that the authors() method returns a list of authors and we’re only taking the first one.

To insert the book, we first look for the author in the database by getting an author resultset and using the find_or_create() method to either find an existing author record or create a new one. Once we have the author object we can use its add_to_books() method to add a new book related to that author. The add_to_books() method is one that was created automatically by DBIx::Class::Schema::Loader when it created our classes. It knew that this relationship between the tables existed because of the foreign key constraint that we created on the book table.

We can now try adding a book to our database. Get the ISBN of a book from Amazon and try running the command.

|

1 |

$ ./book add 0330258648 |

Listing the Books

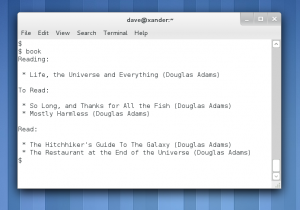

The next sub-command we’ll implement will be ‘list’; so that we can see what is in our database. This looks complex, but actually, it’s rather repetitive as we print the list in three sections (‘Reading’, ‘To Read’ and ‘Read’). The only difference between the sections is the selection criteria we use. Books being read have a value in the started column but a null ended column. Books that have been read have a value in ended. A book with a null started is still in the to be read pile. To run these queries we use the search() method on a book resultset object. A null value in the database is represented by the undef value in Perl.

The reading query looks like this:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

foreach ($books_rs->search({ started => { '!=', undef }, ended => undef, })) { say ' * ', $_->title, ' (', $_->author->name, ')'; } |

The search arguments say that started is not null and ended is null. For each book found by the query we print the title and the author’s name. Again, these methods are created for us by DBIx::Class::Schema::Loader using information it finds about the columns in the tables and the relationships between tables. For the list of books read, the query looks like this:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

foreach ($books_rs->search({ ended => { '!=', undef }, })) { say ' * ', $_->title, ' (', $_->author->name, ')'; } |

And for the list of books still to read, it looks like this:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

foreach ($books_rs->search({ started => undef, })) { say ' * ', $_->title, ' (', $_->author->name, ')'; } |

The full version of the list() subroutine is on the CD.

Starting and Finishing a Book

The last two sub-commands we need to implement are start and end to indicate when we start and finish reading a book. They are very similar so I’ll just show the start one here.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

sub start { my $schema = get_schema(); my $books_rs = $schema->resultset('Book'); my $isbn = shift || die "No ISBN to start\n"; my ($book) = $books_rs->search({ isbn => $isbn }); unless ($book) { die "ISBN $isbn not found in db\n"; } $book->started(DateTime->now); $book->update; say 'Started to read ', $book->title; } |

A lot of this looks very standard by now. We check we’ve been given an ISBN number and then we get a schema object and a book resultset object. We use the search() method to get the book object from the database (and die if it can’t be found). Then we use the started() method to update that column and call the update() method to save the changes back to the database.

When we set up our database classes using dbicdump we asked for an extra component called InflateColumn::DateTime to be included. This is where we see the advantage of that. This component identifies any date and time columns in the database and converts those values into Perl DateTime objects in our program. So we can create a Perl DateTime object using the class’s now() method and DBIX::Class will automatically convert that into the appropriate string to be stored in the database.

The end sub-command looks very similar to this, with only the column named changed from started to ended.

Trying It Out

We now have a working system. We can add books, start reading books, finish reading books and see what the current state of our reading list is. Having already added a book to the system above, try running the following commands.

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

$ ./book list $ ./book start 0330258648 $ ./book list $ ./book end 0330258648 $ ./book list |

You’ll see the book moving between the different sections of the report.

More Info: The CPAN – Perl’s killer app

If you’re programming in Perl then you need to know about the Comprehensive Perl Archive Network (or CPAN). On the CPAN you’ll find almost 100,000 extra Perl modules that you can use in your programs.

The CPAN is at http://www.cpan.org/, but most people use the search page at http://search.cpan.org/. A new project called MetaCPAN (at http://metacpan.org/) aims to provide a better interface and an API.

A large number of the most useful CPAN modules have been repackaged for popular Linux distributions and this will be the easiest way to install most modules. For example, if you want to install the DateTime module on a RedHat or Fedora system you just need to run sudo yum install perl-DateTime. On a Debian or Ubuntu system that command becomes sudo apt-get install libdatetime-perl.

More Info: Object Relational Mapping

Many programs are going to need a persistant data store and in many cases that will be a relational database like MySQL or SQLite. In order to talk to these databases you’ll need some kind of database interface (like Perl’s DBI module) and a lot of SQL scattered throughout your code.

Object relational mapping (ORM) allows you to write code that interacts with a database at a higher level. You no longer write SQL. You just manipulate objects in your program and the ORM layer takes care of converting that code into SQL.

Three concepts in Object Oriented Programming map rather well onto matching concepts in relational databases. In OOP, a class defines a type of object (like books) and that’s very similar to a table in a database. A particular instance of a class is an object (a particular book) and that’s like a row in a database table. Finally, classes and object have attributes which are the individual properties of the object (for example title and author) and this is similar to columns in a database.

An ORM uses these similarities to map data from relational databases into OOP objects within your program. A good ORM like DBIx::Class, the one we are using in this project, will be able to automatically generate the classes from the metadata stored in the database which describes the various tables.

Dear Mr Cross, Thank you for your article. I am new to the DBIx::Class and am trying to learn it. You make mention of the fact that the “…full version of the ‘list’ subroutine is on the CD.”. What CD are you referring to? How would one acquire this. I appreciate your consideration in this matter. Have a great day. Thank you.

Sincerely,

-Paul

P.S.

I have no web site URL to share.

Hi Paul,

Thanks for your comment.

The CD that I’m referring to is the free CD that came with the magazine that the article was originally published in.

All of the code from the project is available from the Github repository at https://github.com/davorg/Book-Demo-App

Unfortunately, the code in the repo is for the finished app, which doesn’t include the list() function (as I removed it when I turned the command line app into a web app). But the repo also contains the tarballs of code that I sent to the magazine. You want the one from issue 151.

Hope that helps.

The Amazon URL mentioned above (www.amazon.com/gp/aws/registration/registration-form.html) is no longer valid.

Looking at aws.amazon.com/free there are a dizzying number of possible services to try for free or for 12-months, or short term trials.

Which among them would be best applicable to the example above?

Please advise,

Al