In last month’s article, we built a simple command line program to manage a reading list. We could add books to the list and note when we started and finished reading them. At any time the program would display a list of books that we were reading, that we had read and that were still waiting in the pile.

Command line programs aren’t particularly pretty though. It would be nicer to display these lists on a web page. Perl is, of course, a great language for doing this and in this article we’ll build a web application that displays our reading lists.

We’ll be using the Dancer framework to build our page. Dancer is one of a number of Perl frameworks that are available. See the box for a brief discussion of some of the alternatives. I’ve chosen Dancer as it seems well-suited to the simple web page we’re going to build here. [Note: There is now a Dancer2 which I would recommend over Dancer. Differences in the code between the two versions are trivial.]

Gathering Your Tools

As well as the modules we installed last month, we’re going to need some more modules from CPAN (https://metacpan.org). Not least of these is Dancer itself. Fortunately, Dancer is available from the package repositories of most major Linux distributions so you’ll just need to run “yum install perl-Dancer”, “apt-get install libdancer-perl” or something similar for your version of Linux.

The Dancer installation includes a number of useful Dancer tools, but we’ll also need one which is distributed separately on CPAN. This is called Dancer::Plugin::DBIC and will make it easy for us to take the DBIx::Class libraries that we built in the previous article and use them with Dancer.

The First Dance

Dancer makes it easy to start writing a web application. When you installed Dancer you got a command line program called “dance” which helps you to create the skeleton of an application. All you need to do is to type

|

1 |

$ dancer -a BookWeb |

This will create a directory called BookWeb and fill it with the beginnings of a Dancer application. Move into this directory and take a look at the files. We’ll be editing these files later, but already Dancer has given us enough to demonstrate a running program. One of the directories created was called ‘bin’ and within that directory you’ll see a single file called ‘app.pl’. That’s our web application. So let’s run it.

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

$ ./bin/app.pl [29957] core @0.000009> loading Dancer::Handler::Standalone handler in /usr/share/perl5/vendor_perl/Dancer/Handler.pm l. 41 [29957] core @0.000274> loading handler 'Dancer::Handler::Standalone' in /usr/share/perl5/vendor_perl/Dancer.pm l. 366 >> Dancer 1.3072 server 29957 listening on http://0.0.0.0:3000 == Entering the development dance floor ... |

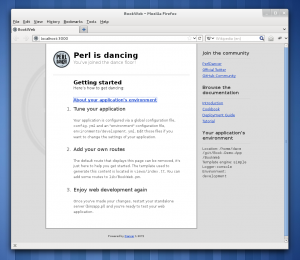

If you open a browser and visit http://localhost:3000/ you’ll see your application. It doesn’t do very much right now but it looks pretty and the page contains useful links to pages that will help you to learn more about Dancer.

Creating Our Web Pages

The first thing that we are going to do is to undo all of that nice HTML formatting and replace it with our own pages. The HTML is stored in two files. There’s a layout file in views/layouts/main.tt and the content of the page is in views/index.tt. There is also a stylesheet in public/css/style.css.

Immediately, you can see a split between where Dancer stores its output files. Files that are processed in some way to produce output are stored under ‘views’. Static files like stylesheets and images are stored under public.

Open the file views/layouts/main.tt in a text editor. All we’re going to do here is to remove the line that loads jQuery. Our application won’t get complex enough to use Javascript so this is unnecessary.

Whilst editing the file, notice the ‘<% content %>’ tag that follows the HTML <body> tag. This is an example of a Dancer Template tag. Tags are processed by Dancer and replaced with other text. The <% content %> tag will be replaced by the contents of whichever template is used for the current request.

In this example we’re only dealing with a single request and that’s a request for the index page of the application. The template for that page is views/index.tt and that’s the next file we need to look at.

It’s really up to you how much you change this file. I removed most of the text, left a few of the div elements and changed the headers. My file ended up looking like this.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

<div id="page"> <div id="sidebar"> </div> <div id="content"> <div id="header"> <h1>BookWeb</h1> <h2>Here's your reading list</h2> </div> </div> </div> |

At Last Some Perl

But this is supposed to be a Perl tutorial, so it’s about time that we wrote some Perl code. We know that bin/app.pl is the file that drives the program, but if you look in there you’ll see that it’s very simple.

|

1 2 3 4 |

#!/usr/bin/env perl use Dancer; use BookWeb; dance; |

It loads the Dancer library and the BookWeb library and then calls Dancer’s ‘dance’ function. All of the real work goes on in the BookWeb library. And that lives in the lib/BookWeb.pm file. So let’s have a look at that.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

package BookWeb; use Dancer ':syntax'; our $VERSION = '0.1'; get '/' => sub { template 'index'; }; true; |

Again. there’s not much there yet. But you can see how Dancer responds to requests. In a Dancer application, you define a number of routes and the Dancer request handler matches each incoming request against the definitions of the routes and runs the code associated with the first route that matches.

A route is a combination of an HTTP request type (GET, POST, etc) and a path. Currently, we only have one route defined which handles a GET request to the root of our application. Any request that doesn’t match that definition will be handled by Dancer’s default “resource not found” handler which will send a 404 response to the browser.

If a request does match the route then the code associated with that route is run. In this case that just interprets the index template that we just cleared out. A lot of Dancer’s power is in the new keywords like “template” that it makes available to your application. The template keyword hides quite a lot of work – searching the filesystem to find the templates, dealing with the expansion of variables and embedding the content templates inside the layout template.

So if we want to put useful things into our web page we need to pass variables to the template call. Specifically, we will want to pass in the lists of books that we are reading, have read and are planning to read. The call will then look something like this.

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

template 'index', { reading => \@reading, read => \@read, to_read => \@to_read, }; |

We’ve added another parameter to the template call. This parameter is a hash which contains details of the data we need while processing the template. The keys of the hash are names that we can use within the template (‘reading’, ‘read’ and ‘to_read’) and the values are references to arrays of books. Actually they are references to arrays of books as you can’t store an array in a Perl hash, but you can store a reference to an array. See the “perldoc perlreftut” manual page for more explanation of this.

Getting Data Out Of A Database

The next thing that we need to do is to populate those arrays. And, as we did in the previous article, we’re going to get that data from our database. And we’re going to use the Object Relational Mapper DBIx::Class in the same way as we did last time.

Dancer has a number of plugins available on CPAN and one of them is called Dancer::Plugin::DBIC. That will give us a ‘schema’ keyword which allows us to get easy access to the DBIx::Class schema object that we use to talk to the database.

Once we’ve installed Dancer::Plugin::DBIC from CPAN we need to configure our Dancer application to use it. We do that by editing the config.yml file which is in the BookWeb directory. At the end of this file, add the following lines.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

plugins: DBIC: book: schema_class: Book dsn: dbi:mysql:database=books user: books pass: README |

You’ll recognise this as the connection information that we used to talk to the database last month. The only new information is the ‘schema_class’ value which is the name of the Book.pm class that we created to enable us to interact with the database. Our new application will need access to that class and the easiest, if slightly lo-tech, way to achieve that is to copy the Book.pm into the applications lib directory. You’ll also need to copy the Book sub-directory that contains the other database classes (Book/Result/Author.pm and Book/Result/Book.pm).

While you’re editing config.yml you should also change the template engine. Dancer comes with support for two templating engines. The default engine is a simple one that isn’t quite powerful enough for our needs, so we need to change to use the template toolkit. Do that by changing the template section in config.yml to look like this.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

# template: "simple" template: "template_toolkit" engines: template_toolkit: encoding: 'utf8' start_tag: '<%' end_tag: '%>' |

Notice that we’ve changed the template toolkit’s start and end tags from ‘[%’ and ‘%]’ to ‘<%’ and ‘%>’. That’s because our existing templates already contain these tags.

With these libraries in place we can finally write code that accesses the database. Change BookWeb.pm so that our route looks like this.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 |

get '/' => sub { my $books_rs = schema->resultset('Book'); my @reading = $books_rs->search({ started => { '!=', undef }, ended => undef, }); my (@read, @to_read); template 'index', { reading => \@reading, read => \@read, to_read => \@to_read, }; }; |

We’re using the ‘schema’ keyword to access our schema object, but the rest of the database code is exactly the same as the code we used last time. We get a book resultset object and then use its ‘search’ method to get an array of the books we are interested in. Books that we are currently reading have a not null value in the started column and a null value in the ended column. We’ll ignore the other two lists for now and we’ll look at how we deal with the data inside the index template.

Templating The Output

Here is what the index.tt file looks like once I’ve added code to handle the ‘reading’ array.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 |

<div id="page"> <div id="sidebar"> </div> <div id="content"> <div id="header"> <h1>BookWeb</h1> <h2>Here's your reading list</h2> </div> <h3>Reading</h3> <% IF reading.size %> <ul> <% FOREACH book IN reading %> <div class="book"><p><img src="<% book.image_url %>" /> <a href="https://amazon.co.uk/dp/<% book.isbn %>"><% book.title %></a> <br />By <% book.author.name %></p> <p><% IF book.started %>Began reading: <% book.started.strftime('%d %b %Y') %>.<% END %> <% IF book.ended %>Finished reading: <% book.ended.strftime('%d %b %Y') %>.<% END %></p> </div> <% END %> </ul> <% ELSE %> <p>No books found.</p> <% END %> </div> </div> |

The interesting bits are in the <% … %> tags. You’ll see an if/else statement and a foreach loop. These are both standard programming constructs that act as you would expect. The hash of variables that we passed into the ‘template’ call had a key called ‘reading’ and that becomes the name that we use to refer to that data inside the template. As the variable is an array we can call a ‘size’ method to see how many elements it contains. If the array is empty, the if condition is false (Perl treats zero as a false value) so we execute the else code which displays ‘no books found’. If there are books in the list then we iterate over the list putting each book in turn into a temporary variable called book.

Each of these book values is a DBIx::Class book object like the ones we used in the previous article. And that means they all have methods for each of the columns in the database table. We can use those to print the title and the author’s name. We also use the books’ ISBN to construct a link back to the books page on Amazon. Notice that the ‘started’ column returns a Perl DateTime object so that we can use that class’s ‘strftime’ method to get a nicely formatted date.

In order to make the page look a little more attractive, we can add the following tweaks to the stylesheet in public/css/style.css.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

img { float: left; margin: 0 5px 5px 0; clear: both; } .book, h3 { clear: both; } |

All we need to do now is to write the code to retrieve and display the other two lists – the list of books we have read and the list of books we haven’t started. But that’s going to get a little repetitive, so before we do that, let’s make a few changes to the index.tt to make our life as easy as possible.

The Template Toolkit has the concept of ‘macros’. These are a bit like functions in the templating world. They make it easy to bundle up and reuse repetitive code. We can define a ‘showbook’ macro that defines how we display a book and then just call it whenever we want to show the details of a book. Here’s the macro.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

<% MACRO showbook(book) BLOCK %> <div class="book"><p><img src="<% book.image_url %>" /> <a href="https://amazon.co.uk/dp/<% book.isbn %>"><% book.title %></a> <br />By <% book.author.name %></p> <p><% IF book.started %>Began reading: <% book.started.strftime('%d %b %Y') %>.<% END %> <% IF book.ended %>Finished reading: <% book.ended.strftime('%d %b %Y') %>.<% END %></p> <% END %> |

It’s exactly the same code as we used before, just bundled in the MACRO … BLOCK … END syntax that makes it reusable. With this block added to the top of the index template we can write the section that actually displays the books like this.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 |

<h3>Reading</h3> <% IF reading.size %> <% FOREACH book IN reading %> <% showbook(book) %> <% END %> <% ELSE %> <p>No books found.</p> <% END %> <h3>Read</h3> <% IF read.size %> <% FOREACH book IN read %> <% showbook(book) %> <% END %> <% ELSE %> <p>No books found.</p> <% END %> <h3>To Read</h3> <% IF to_read.size %> <% FOREACH book IN to_read %> <% showbook(book) %> <% END %> <% ELSE %> <p>No books found.</p> <% END %> |

Each section is exactly the same; they just work on different arrays.

All we need to do now is to fill in the values of the ‘read’ and ‘to_read’ arrays that are passed to the template. We wrote code that did this in the previous article and we just need to replicate that in the route in BookWeb.pm. When we’ve finished, the complete route definition will be like this.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

get '/' => sub { my $books_rs = schema->resultset('Book'); my @reading = $books_rs->search({ started => { '!=', undef }, ended => undef, }); my @read = $books_rs->search({ ended => { '!=', undef }, }); my @to_read = $books_rs->search({ started => undef, }); template 'index', { reading => \@reading, read => \@read, to_read => \@to_read, }; }; |

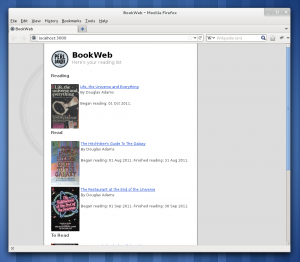

We still have to update the database using the ‘book’ command line program that we wrote last time, but now we have an attractive web version that we can use to display our current reading list.

More Info: Web Frameworks in Perl

Writing a web application is a complex process, but using a framework can make the job much easier. There are a number of web frameworks available for Perl. You can get them all from CPAN.

In this article we have used Dancer. Dancer is based on the Ruby framework, Sinatra. It defines a web application as a number of routes which are the HTTP requests that the application will respond to. This approach makes it very easy to get an application up and running quickly. You can get more information about Dancer at http://perldancer.org/.

The best known Perl web framework is Catalyst. Catalyst is a very powerful and flexible framework. It is the framework behind a number of well-known web applications. Its web site is at http://www.catalystframework.org/.

Another alternative is Mojolicious. Mojolicious concentrates on making things as simple as possible while not compromising on power or flexibility. You can find out more at the project’s web site at http://mojolicio.us/.

More Info: The Template Toolkit

In this example, we’ve used the Template Toolkit to build the HTML pages for our application. A templating engine is an essential tool for building a web site of any complexity. A good templating engine will make it easy to separate the business logic of your application from the logic that displays the data to the users.

The Template Toolkit is generally accepted as the most powerful and flexible templating engine for Perl. It has its own simplified display language, but a plugin system gives you easy access to much of the power of CPAN. Version 2 of TT has been around for several years, but version 3 is now getting close to being released.

TT has a web site at http://tt2.org which is not only a useful resource, but also a demonstration of the power of the toolkit. There is also a book, Perl Template Toolkit which is published by O’Reilly.

More Info: Routes in Dancer

I’ve said that Dancer is built around the concept of routes, but what exactly is a route and how does Dancer use them?

A route is the combination of three things: an HTTP request method, a request path and some code. When Dancer matches an incoming request with the method and the path, it runs the associated code.

In our example, this was the definition of the only route.

|

1 |

get '/' => sub { ... }; |

In this example, ‘get’ is the HTTP method, ‘/’ is the path and the code is defined in the subroutine. When Dancer sees an HTTP GET request to the path ‘/’ (i.e. the root of the web site) the code is run.

All parts of the route definition can be more complex. You could match a POST request with the ‘post’ keyword or either any HTTP request method with ‘any’. You can also access data passed in the request path using code like this.

|

1 2 3 |

get '/hello/:name' => sub { return "Hello " . params->{name}; }; |